Two weeks ago I attended the third annual “Leadership for School Improvement Colloquium” held at the Catholic Leadership Centre in Melbourne. I was a first time attendee and felt proud and privileged to be a part of a wider Catholic network of system educational leaders committed to school improvement.

As a participant at the colloquium I left with a number of reflections, most particularly that Catholic School Offices across the country have effectively refined their system-led school improvement (SI) processes through extensive use of quantitative measures and regular ‘check-in’ processes. Most pleasing is that goals of improvement are quite rightly linked to student learning outcomes with some SI processes able to access data dashboards and even put faces on the data. Also pleasing, is the spirit behind the process. Data is being used to promote dialogue and engage in a spiral of inquiry about improved student learning outcomes rather than to offer judgement through inspection. This is very different from the league table approach adopted by headline seeking media outlets!

As a result of my participation at the colloquium, it was obvious to me that Catholic education systems across the country, not unlike Government school systems and Independent school systems, have worked tirelessly, effectively and successfully to implement structures and processes which focus on, support and achieve school improvement. The SI agendas within most systems are usually advanced through timelines, policies, programs and structures as part of a well planned and system-led process, sometimes perceived by some school leaders (rightly or wrongly), to be rich in system accountability and light on school autonomy. I am not suggesting we change SI processes; however, I do ask myself…..

“Do highly effective School Improvement processes stifle innovation in schools?”

The inspirational Martin Luther King had a dream, he did not have a improvement plan. As per Greg Whitby’s latest blog, “Improvement is no longer the Challenge”, Steve Jobs’ dream started with Apple changing focus from ‘manufacturing’ to ‘lifestyle’. What a profound shift this turned out to be! The great companies of the world such as Apple have short, sharp, succinct Vision statements to which all actions, structures and resources strategically align. Bristol-Myers aims “To discover, develop and deliver innovative medicines that help patients prevail over serious diseases”. Amazon strives “To be earth’s most customer centric company; to build a place where people can come to find and discover anything they might want to buy online.” I am unsure if these companies have detailed strategic plans or extensive ‘improvement processes’. If they do, they don’t appear to suggest improvement plans are central to their success.

Education systems, and schools within those systems, need to wrestle with the relationship between ‘improvement’ and ‘innovation’. Do school improvement processes inspire schools and systems to strive for innovation? Can they co-exist? Possibly, but I suggest that innovation in schools not be aligned to system-led School Improvement Processes. I suggest that

“Innovation be linked to a Vision, or even a Dream developed by schools and centred on the development of skills for students of today for when they are employees in 10 years from now.”

The recent Report: The New Work Order, published by Foundation for Young Australians (2015), paints an intriguing picture of work in 2025. There are immediate implications for what schools provide for our current students, and how it is provided. I sense more ‘innovation’, not more ‘improvement’, will be required to respond to the challenges inherent in this report.

In saying this, there are promising signs regarding innovation in schools. Firstly, there have been Schools Rethinking Education with an innovative mindset for quite some time – and they are not seeking forgiveness! Currently, there is a groundswell of schools within the system where I work, who are keen to pursue an ‘innovation agenda’. This is acknowledged and accepted by our system leaders. Some/most schools leaders are seeking permission to ‘think big’, even ‘Do, then Think’; something which may be considered a departure from a deep inquiry of searching for a problem in response to quantitative data. On the other hand, if we need a problem to start an ‘innovation inquiry’ I don’t think we have to look too far. The data, through many reports including OECD reports, project into the future workplaces our students will enter. The New Work Order Report goes some way to explaining that future. The conclusion is that the education being provided in Australian schools needs to be dramatically different, even transformed, if we are to prepare students for very different world of work. There is a clearly defined problem and that problem is,

“schools are not developing and nurturing the skills that students will need when they become future employees.”

A few years back I reflected about what some companies of the world do regarding innovation and tried to link that to Unstructured and Non-Commissioned Time for Teachers. The thinking (and considerable proof) is that unstructured time supports and enables new ideas for innovation. For example, Google 80/20 time is not aligned to any company plan; yet some of their applications, including gmail, have been an outcome of the 20% individual ‘free time’. The 80/20 principle may not be the panacea as articulated in Chris Townsend’s post Innovate or Die but such a strategy does provide a lever to think and act differently. Companies are not schools, but we can learn from them. In his post Townsend writes, “to see the light of day, innovations typically require at least some degree of resources (funding, staffing, specific expertise), and both operational and functional support and buy-in.” I suggest the “operational and functional support” for innovation offered by systems who specialise in school improvement is wedded to tried and true methods of “improvement rather than a deeper understanding of how to create sustainable ‘innovation’ discipline across the enterprise.”

If school systems are looking to facilitate innovation within the community of schools for whom they serve, then we need to offer alternatives to the ‘improvement approach’. This starts with the data we use. Measuring ‘innovation’ may be a lot harder to do than measuring ‘improvement’; however, I suggest we start by valuing innovation as much as we do improvement. It is not an either/or! It is ‘improvement’ AND ‘innovation’ but we must engage with them, and measure them, in different ways but with equal importance.

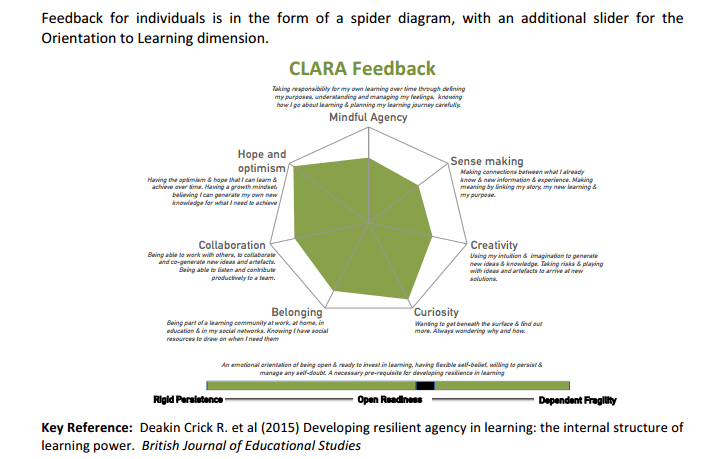

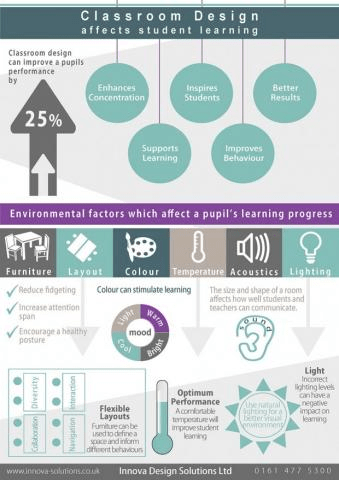

Where to start? Systems could commence the process by re-calibrating their focus to support teachers to relearn their role by pursuing 8 things every teacher can do to create an innovative classroom. Another option could be to pursue “innovation across the enterprise” by measuring contemporary learning traits and mindsets of students through the use of school developed rubrics which focus on skills such as collaboration, or the Australian Curriculum General Capability of Critical and Creative Thinking. These rubrics would be applicable to all subjects across multiple year levels. Another idea might be to measure how students gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures, knowledge traditions and holistic world views. In an attempt to measure a school’s ability to develop globally responsible citizens (a buzz phrase some schools use for promotional purposes) there could be an attempt to measure the priority of Australia’s engagement with Asia by measuring students’ ability to celebrate the social, cultural and political links with Asia, and how students apply that knowledge in a globally connected world.Measurement of these priorities may already be happening in some schools, but are they being valued to the extent that they are system embedded?

‘Innovation’ is usually an outcome of iterative, messy, unstructured processes – this is different to the rigorous structures associated with school improvement. I argue

the advancement of the ‘innovation agenda’ requires a new mindset, new structures and maybe even new personnel driving something which is seen to be ‘different’ by the teachers and principals in the schools those systems serve.

This is challenging to those of us ‘in system’ but through conversations at the Leadership for School Improvement Colloquium it pleasing to note some system leaders are facilitating school based innovation initiatives. I am also pleased to say I am working in one of those systems with some of those system leaders. Hopefully, a rich story is yet to be told about that!

Regardless of the individual ‘innovation narrative’, I strongly believe all education systems who oversee a community of schools need to pursue, support and encourage innovation. In doing so, it needs to be done in such a way that is different from well established school improvement structures and processes. If not, we run the risk the ‘innovation agenda’ will be restricted, even negated, from being too tightly aligned to SI processes, indicators and thinking. I am sure no-one wants to see ‘innovation agenda’ be defeated by the well developed ‘school improvement’ agenda. They can co-exist, but through different approaches.

Regards

Greg